The Concept behind the Methodology

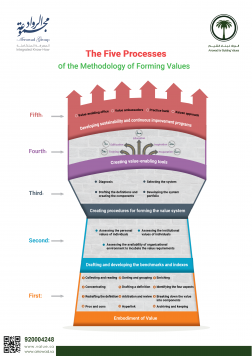

Our scientific methodology caters to scholars, consultants and professionals specializing in developing theoretical frameworks, practical guides and hands-on programs. The methodology includes five key processes:

These five processes are not procedural methodological stages for instilling and promoting values. They are rather meant to be methodological scientific processes preceding and laying the foundation for the procedural services provided to the clients of all types and in any environment. For each process, there is a procedural handbook and guidelines to assist scholars as well as employees of institutions in implementing their assignments.

Value-Building Processes

In this part, we will extensively explore the five processes and cover all value building and enabling matters. This offers a solid ground on which field practitioners can work to generate knowledge and develop practical programs.

A general understanding of values is a product of the theoretical and intellectual frameworks as well as well as practical applications. However, these did not produce a well-defined entity that divides a value into components, subcomponents, behavioral indicators to be acquired by individuals and organizational procedures for creating an incubating environment. Nevertheless, a value was a mere abstract concept that is hard to digest.

We believe that embodiment of values is the best way to transform perception values from an abstract concept into a logical meaningful one applicable by individuals. Embodiment is key pillar of value formation. Embodiment is transforming the abstract meaning of a value into a well-defined entity. To do so, we need to define the value and identify its components and relevant and contradicting behaviors. It also requires analysis of the component dimensions and pinpointing the merits of adoption and outcomes of negligence. In addition, we create assessment tools, behaviors and procedures of adopting and acquiring the value and eventually introduce hands-on value-enabling procedures that facilitate transforming the value from mere mottos to reality.

Embodiment of value, particularly the corporate values, is the basis of the entire formation processes. This process is implemented in a sequence of tasks while each task or set of tasks lead to a specific outcome. We developed a practical manual to guide and assist researchers in defining a value and analyzing its components and subcomponents. The manual demonstrates the positive impact of adopting the value system and the positive returns collected by an organization once it creates a value-supporting environment. Afterwards, it highlights the risks and threats failure to adopt genuinely the values or to provide the supporting procedures might cause. This stage aims at emphasizing the individuals’ affective aspect and appreciation of values. Consequently, the concerned individuals could acquire and defend the values. Another value embodiment process is clarification of the benchmarks that indicate when an individual has embodied a value as well as the procedures required from an organization to prepare a value-enabling environment.

The purpose of the manual is assisting value-enabling researchers in developing and drafting benchmarks, value-enabling programs and training and informative material that create an impact in the service’s target audience.

To the best of our knowledge, the Embodiment of Values manual is an unprecedented scientific feat in the whole world. During our research, none of the books, references or articles had covered the value embodiment subject matter nor been there a dedicated methodology or handbook for researchers to utilize. Section Four of this book titled Practical Models covers the manual in detail.

Personality can be assessed and evaluated in a variety of methods and by various tools, the most significant of which are surveys. There are two types of surveys, the first of which assesses values by means of an array of multiple-choice questions. An example of this is the Value Survey by Allport and Lindzey that measures six values (aesthetic, theoretical, economic, societal, religious and political). Another example is the Measurement of Differential Values by Prince, R, 1957, which specifies two types of values, namely traditional and emergent. It has 67 statements each of which has a contradicting item, i.e. one representing a traditional value while the other represents an emergent one. The respondent will choose either of the statements.

The second survey type is measuring values by means of ranking order scaling. An example of this type is Rokeach Values Survey including 18 terminal and 18 instrumental values. The task for participants in the survey is to arrange each of the values into an order of importance. Another example is the Personal Values Inventory developed by Lovat, T., and Hawkes, N. (2013); the Goal and Model Values Inventories by Braithwaite, V. A., and Law, H. G. (1985); the Value Profile by Bales, R. F., and Couch, A. S. (1969) to name but a few. All of these surveys mostly focus on measuring an individual’s personal values.

The majority of approaches to measuring corporate values assume a value set based on specific theoretical principles on which they were founded. For instance, Woodcock, M., and Francis, D., (1980) Organizational Value Survey (the most common in this area) incorporates a number of values characterizing a successful organization. They reached this conclusion following several studies conducted in many countries. They also observed that corporate values are quite similar across cultures. Alongside the theoretical value studies and classifications, implementation of some noteworthy international surveys contributed to promoting a culture of measuring personal, corporate and societal values. Individuals as well as organizations became aware of the significance of value measurements.

Some of the most prominent surveys are the personal, organizational, school and societal assessments administered by Barrett Values Centre located in the United Kingdom. These assessments utilize the Barrett Model comprising the Seven Levels of Personal Consciousness. The model was introduced around 1996/1997 and is based on the premise that human develops across seven specific areas. Each area emphasizes a specific need common among all people. How a person matures and grows is reliant on the extent to which he/she caters for each need and on passage of time. The model identifies only 66 values.

The World Value Survey is a global research project conducted by a network of social scientists. It explores the impact of changing values on social and political life.

Having reviewed most approaches to and tools of value measurement, we appreciate the massive efforts exerted on cognitive theoretical basis. However, we believe that these have three drawbacks.

All assessment approaches presumed specific values in light of the theoretical frameworks on which they are based. The adopted principles were the foundation of assessments that measure and survey individual, corporate and societal values. In our opinion, this represents a drawback for the fact that values in spite of being global are different in each individual, organization and society. In other words, they are personal, organizational and societal preferences. Hence, these assessments cannot be generalized across individuals, organizations and societies.

In addition, a particular set of values are classified into specific groups then given different names. This practice means that one value can be referenced in several groups. For instance, friendliness, patriotism and tolerance are collectively referred to as ethical values. However, all or some of these values are found in other groups. For instance, patriotism is also a national value and so forth.

There is a controversy among researchers concerning repetition of one value in several groups. Subsequently, the controversy is carried over to the assessments and interpretation of their findings.

Another drawback is that these assessments are primarily developed to measure personal values and identify the prevailing personal value system of individuals. Nevertheless, they are used to assess corporate values, which may not be assessed through personal values. Assessments of corporate values measure the extent to which an individual adopts and acquires the corporate values (and do not measure his/her personal values), on the one hand, and the extent to which the organization provides the requirements of the values it declares and adopts, on the other.

The third drawback is the discrepancy in assessing the conformity of personal with corporate values. This case is evident when assessments ask individuals to evaluate the extent to which their personal values conform to corporate values. For instance, a survey might ask: “I agree with the values of my organization” or “The things I appreciate in life are similar to those appreciated by my organization”. On the contrary, a survey might question respondents to think of how related the survey questions are to their current working environment. The same survey yet might ask the respondents to assess how close the survey questions can describe his /her own personality.

Upon thorough investigation of the questions in these surveys, it was found that they remotely resemble personal and corporate values. The questions are descriptive statements generally describing values and to whom they relate in the corporate environment. To elaborate, they do not particularly cover a certain value such as integrity, being a personal value prioritized by individuals. Conformity is assessed, in this case, through first identifying the personal values of an individual (i.e. integrity, teamwork etc.), and then assessing the significance he/she associates to the declared corporate values (transparency, integrity etc.) and finally measuring the conformity between them both.

Plenty of research and studies on forming personal values systems reference previously developed systems and recommend them to individuals. These systems mostly consist of general values representing the exemplary situation of a sound personality that every person aspires to be. However, it is uncommon for researchers to elaborate on developing practical procedures for forming a personal value system that caters for the goals, capabilities and priorities of the concerned individuals.

When forming the family value system, researchers often confuse it with the personal value systems of family members. Some studies introduced ready-made model systems that work for all families and represent the ideal family value system. Still, they did not provide practical procedures for forming a family value system that addresses the particularities and priorities of each family.

As for forming an educational value system (for learning and teaching), it often lacks a clear and precise philosophy. In addition, it does not integrate values into all the elements and phases of education including the curriculum and teacher-oriented value training. Moreover, the majority of relevant research lean towards excessively following the values alluded to in the curriculum rather than developing curricula in light of previously formed values that suits the educational institution’s vision.

When it comes to forming the corporate value system in the public and private sectors as well as the non-profit organizations, no strategic plan developed by corporate consultants could hardly emit a value system. Nonetheless, these are often made in a hurry and are not founded on a thorough study of the institution’s reality nor employees’ situations. Besides, it is unlikely that corporate value-enabling programs are given any attention. Organizations do not pay close attention to the requirements they should meet for preparing a value-supporting environment. (Since it is an essential and common task nowadays, forming corporate values will be cover in details in Section Four of this book.) This also applies to forming the national values. They are extensively covered and referenced in constitutions and laws in all countries, yet are not based on an agreed-on national value system. If they do, all authorities and bodies would work on enabling and instilling them into the citizens.

Research, studies and papers on the subject of values theoretically covered the methods of instilling, reinforcing and acquiring values. Eventhough, all this literature emphasized the importance of values, it typically did not offer practical tools for instilling or reinforcing values nor clarified how to achieve this end or its significance but narrowly. A few researchers and organizations made limited contributions in that area; an applauded effort that helped in transforming the theoretical ideas into real-life practice.

We looked at and utilized some of these studies, programs, projects and tools. Most of these resources consider that there are three aspects to the value instilling and acquisition process, namely parental upbringing, model mimicking (role model) and direct exposure through training and education. We fully agree on all these aspects. Nonetheless, we did not dive into theorization nor solely focus on the value instilling and acquisition process. We profoundly emphasized on creating a scientific methodology and practical tools aimed at creating a model inclusive of acquisition and instilling process. We call it Value-Enabling.

In this context, sustainability means sustainable effort and impact. In other words, it is the continuous serious efforts to review and improve the institutional values. It also includes the ongoing value-enabling processes across many streams comprising the institution as a whole, leaders and employees. Sustainability is building the capacity of the officers who manage the corporate values so that they could sustain the enabling processes. Sustainability can be approached through a number of procedures such as introducing a value management office, value ambassador program, developing value-based practices and Kaizen approach to continuous improvement.

Through experience and hands-on application (and since we conducted a number of consultations and training projects for a several public and private sector businesses as well as non-profit organizations in which we implemented our value-enabling methodology), two major challenges emerged hindering the sustainability of value-enabling processes in organizations.

First Challenge: We found that the value-enabling responsibility in the organizational structure is vague. Is the strategic management or the human resources team in charge of it? This is due to absence of a dedicated value department in the organizations we worked with. Such a department should be responsible for implementing the value-forming and enabling processes. We also believe this is the case in most other organizations.

Second Challenge: Lack of, and most likely absence of, a caliber qualified to form and enable value systems.

To overcome these challenges and ensure sustainable value-enabling processes, we propose that institutions, irrespective of their type, adopt these two solutions.

Solution to the First Challenge: Initiate the value-enabling department and build its capacities to enable the corporate values. It will undoubtedly bring major benefits to the performance of the organization as well as its employees. Benefits would even reach the stakeholders and society at large.

For better effectiveness and sustainability of the impact by the value-enabling processes, we propose that organizations need to establish a comprehensive scheme for the value management or office in line with their activity and size. The scheme includes all means of realizing the administrative goals including pinpointing the position of the value-enabling management in the organizational structure. The office could report to the strategic department, the better choice in our opinion, or to the human resources in collaboration with the strategic department or be situated as deemed fit by the organization and in line with its executive plans.

Solution to the Second Challenge: In parallel with the first solution, organizations should build the capacities of the caliber assigned to the new value management roles. Qualifying the caliber requires accredited and well-developed training courses so they can implement and improve the value system formation procedures then instill the values into the employees and integrate them into the corporate system.

To the best of our knowledge, capacity-building courses relevant to values are quite scarce. Hence, we are undertaking a massive project aimed at qualifying and building value-oriented capacities and assisting in sustaining the values using a scientific and practical approach. This qualification is the Advanced Diploma in Values and Profession Certificates in Values. If interested in learning about our course offerings, please visit our website www.value.sa

Continuous Improvement is a process that co-exist in parallel with all the five processes of the Formation Methodology. It ensures quality performance of all processes and procedures, examines the outcomes and impact and improves the operations in order to realize the utmost and highest quality performance while being time and cost efficient and effective.

III. Value Stakeholders

When covering the topic of reinforcing, instilling or building values into individuals, the majority of intellectual and theoretical frameworks confuse the roles of three value stakeholder types with one another. The first type is individuals who are responsible for themselves. Then, there are the influencers’ community who are responsible for other individuals and take charge of enabling the values in the supporting environments under their authority. Finally, there are irresponsible influencers who are accountable to no one. However, the latter exercises a huge influence on society as they communicate a value culture and instill values into their audience. It is imperative that these roles are not to be confused with one another since they are stakeholders in the formation process. The figure (10) demonstrates the value stakeholder types.

Formation Methodology in Brief

The foundation of our scientific methodology of forming values is transforming values from abstract concepts into well-defined entities. The first process is embodiment of values followed by drafting the benchmarks and developing the assessments that measure individuals acquire the values. It also involves developing measurements to examine the extent to which an environment meets the value requirements. Afterwards, the value formation procedures are developed succeeded by creating value-enabling mechanisms for each environment, which comprise five streams (i.e. preparation of the supporting environment, inspiration, education, edification and training) in light of scientific, applicable and practical approaches, tools and manuals. Eventually, we develop sustainability and continuous improvement programs tailored to the previous four processes.

These five processes are scientific and concern consultants and scientific researchers involved in developing procedures, assessments and enablers. They are not procedural services offered to institutions in such a sequence since procedures of services have their own sequence and comprise even more processes. In Section Four of the book, we will cover some of these procedures where we opted for the workplace as the environment to which the models are applied.

Adoption of this methodology requires exerting a significant effort, undertaking several thorough tasks and employing a considerable caliber of experts and specialists in these five methodology processes. In doing so, those stakeholders interested in forming values in their environments can realize the desired impact. The figure (11) represents a global view of the methodology processes.